Square, Circle, Amoba – Possible Models of Field Recording and the Auratic Fake was published in “Not Berlin and Not Shanghai”, Transscript, 2009. Until today it is actively performed, e.g. as an integral part of my teaching activities at the School for Music and Media, Duesseldorf (since 2013).

Excerpt:

This essay introduces possible models of on-site acoustic field recording and its particularities.

1. So what exactly is a field recording? While reading these lines, you are probably sitting in a room. Private or public, alone or with people – in any case a space limited by walls, with a ceiling and floor, with a door and possibly windows. Let’s consider this space as a ‘field’ and place microphones in it. We are making a field recording.

The exploration of what constitutes a ‘field’, considered worthy of being documented, began around 1890 with Jesse Walther Fletcher’s research on the Hopi and Zuni of the American Southwest. Since then, field recordings have become an essential component of the field research carried out by ethnologists and ethnolinguists. The second large sector of field recording is – parallel to the concept of photography – phonography, which refers to the recording of natural sounds. Unprocessed recordings of nature and the environment play an important role in today’s natural sciences including newer disciplines such as bioacoustics.

In 1913, field recording found its official entry into artistic practice through the essay ‘The Art of Noises’ by the Futurist Luigi Russolo. Since the early 60s of the 20th century, field recording has gained in influence as a means and medium for compositional work. Almost simultaneously the processing of sounds and sound recordings was found to move into the areas closer to the core of the arts system – mostly in connection with experimental concepts dealing with the architecture of space and time.

With regards to pure, unaltered field recording, defining its boundaries in relation to music, physics, documentary field work and the arts is a matter of each individual listener. But what do you imagine a ‘field’ to be and how could it be outlined as an abstract model? To demonstrate this, we will turn on the microphones and the recorder. We could declare this/any/your room to be a model and thus assume the field was square (ill. 1).

This assumption coincides with certain characteristics: To begin with, a square is the most evident symbol for a ‘field’ as a part of a whole. It has defined boundaries and angles which are calculable. It illustrates a territory possessing measurements and dimensions. It is a closed entity, at least in this particular, most elementary case. You could make yourself comfortable in a corner and continue to think about whether the acoustic field you happen to be in actually is a square. If we now try to ‘listen closely’, a process takes place which can be understood as ‘listening all around you’. The sense of hearing describes a directed circular movement around our head. Angles and corners cannot be perceived. Thus, let’s try using a circle as our next model…

ill.2

Symbolically, the circle stands for an ‘entirety’ or also for ‘the world’. Interestingly enough, it remains unresolved whether we are dealing with the illustration of an inner or an outer world. In any case, the circular model and the square share the qualities of calculability and closeness. But calculability is a characteristic which does not apply to any audibly existing natural surroundings. And besides, nothing real is separated by boundaries. The sounds of the world that lie beyond visually defined borders are also heard. The audible or recordable space has neither square angles nor segments; it may possess ‘intersections’ (to the auditory fields of other persons), but its margins remain blurred. This lacking demarcation is illustrated by means of a variant.

Ill. 3

On the one hand, closeness of the membrane is broken open, and on the other hand, the circle is four-dimensionally shifted around itself. Surface is transformed into space; and the time that is required to evoke the space in this manner is also taken into account. The model Field B/Variant could stand for a spherical space of time within which acoustic phenomena can be perceived and/or recorded. This model could also be considered as the abstraction of an entirety, of which neither the beginning nor the end are recognizable – the world as a field. The model of worlds that touch and are conjoined by membranes reminds us in a highly intriguing way of a foam flake. This basically is quite a useful sketch, though it is indeed so comprehensive that the question inevitably arises, at which point the subject with his microphone should be positioned. Another field could be determined within the maelstrom of multiple penetration, namely that of the perceiving/recording person. It is, however, most unlikely that the documentarist together with his field would accept to be installed in a space located outside of the material physique of the existing world and its acoustic emanations.

Although the dotted arrows in this illustration indicate an interaction between world and person, this concept hardly serves as an appropriate model for a field recording. Whether perception encompasses our world or the world embraces our perception will remain a paradoxical question which does not allow for adopting a fixed position. The ears are – far more than the eyes – a place of interpenetration between the inner and outer world, between the centre and periphery. In order to put an end to speculations on right angles, circular or ball-shaped fields, I would suggest applying an organic model for field recording: the amoeba.

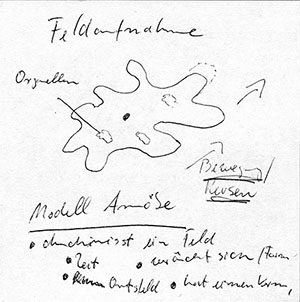

Ill. 5

As a protozoon, the amoeba is classified among the simplest existing lifeforms and thus is well-suited for an abstract model. Other characteristic traits are mobility, mutability, reactivity, blurred boundaries and permeability. Additionally, it includes the aspects of time and space. Let’s assume that the acoustic field surrounding us at any given time resembles an amoeba and the documentarist equals the cell nucleus (regardless of the fact that there also exist amoebas with several nuclei, which, however, isn’t necessarily contradictory to reality). The acoustic field is equipped with pseudopods branching out to various sides, all depending upon what our attention is directed to. Whether it is the shot of a revolver from outside the window, or the clanging of a glass in the kitchen, the field stretches out towards it and tries to envelope the phenomenon, focuses on it and registers it. Each time we move, the surrounding acoustic field moves with us. In this context, the quality of mobility can be understood both actively – a spatial change – and passively, implying a shift on the time axis.

By looking into biological details, the comparison can be pursued further yet: Under the microscope the amoeba appears as a semi-transparent mutable form. To be distinguished are: the usually blurred cell nucleus, the transparent ectoplasm aligning the inner membrane and the endoplasm filling the body along with the organelles required for the osmotic equilibrium and food digestion. There is no fixed relation between the nucleus and the organelles; both change their positions within the field. The indistinctness of the nucleus corresponds to the vaguely circumscribed consciousness of the documentarist, who, in order to ensure proper functioning of the field, fulfils the tasks of equalising tensions (with the exterior world) and processing information.

The amoeba as a possible model of field recording assimilates the aspects of locomotion, indistinctness, permeability, space, time and the particular processes which occur during a recording. The typical dichotomy of interior and exterior, of site and surrounding, does not apply. The same thing happens when we are listening to a field recording. There is, however, another phenomenon appearing in the field which I should like to term the ‘auratic fake’. Thus, if you’ve followed me so far, holding your book, sitting in your room with that real or imaginary microphone, I suggest that you switch off this device. Let’s go to replay and listen to the recording. Our field recording will probably not be too spectacular, consisting of distant music, the murmuring of traffic or perhaps the sound of clothing rubbing against a chair, a dog barking or heavy breathing. Nevertheless: Unlike any other medium, field recording allows the listener to be at two places at the same time. By listening to a field distant to us in terms of space or time, while dwelling in the present- time field of our recording, a doubling effect takes place which may cause confusing disturbances in the flow of our perception. Where does the listening subject begin and where does it end? Between the ears, in this room, in another space beyond?