[Lopsided Towers – La Defense] has its roots in the terrorist attack of 9/11, and two very different cut-up texts sprang up from it: “Schiefe Türme” on occasion of the “Anagrams of War” exhibition/performance in 2002, – and this text, commissioned by the artist Nathalie Grenzhaeuser for her catalogue “Die Große Arche” in 2004. Inspired by Robbe-Grillet’s “Topology of a Phantom City” a dystopic vision of Paris-in-the-Future evolved. Planned as a radio play for 2019/2020.

Published in: Nathalie Grenzhaeuser: Die Große Arche. Forum 1822 Sparkasse, Frankfurt/Main. 2004

Excerpt: (German only)

Paris, Juli 2008, Observations sur La Défense. Enregistrement No. 7

Am ersten Tag der fünften Woche ist die Situation in groben Umrissen also folgende: Ein Steg aus Stahl und Tropenholz führt über 450 Meter vom Foyer der Arche über Gartenanlagen und schlammiges Brachland fort in den leeren Raum. La Jetée, von Osten aus gesehen, wird flankiert vom Friedhof „Neuilly“ zur rechten, dem Friedhof „Puteaux“ zur linken Seite. Es ist seltsam, dass diese Konstruktion, erdacht von dem Ingenieur P. Chemetov, an keinem bestimmten Monument oder einer irgendwie gestalteten Topologie, sondern an einem klassischen urbanen Unort endet. Ein junger Mann, der sich dem Betrachter nicht zu erkennen gibt, lehnt mit geneigtem Kopf über den Rand der Brüstung. Der seit Tagen beständig zunehmende Wind hat den Pappeln, die unterhalb der Jetée im Garten der Arche eingepflanzt sind, schweren Schaden zugefügt: Hier und da lehnen kleinere Baumkronen wie erschöpft zwischen den Metallstreben. Je nach Windstärke schwanken auch die Gebäude des Viertels, eine Entwicklung der Umstände, die von zumeist unbehaglichen Gefühlen begleitet wird. Der Blick des am Geländer lehnenden Mannes ist jedoch nicht dorthin gerichtet, es scheint vielmehr, als ob er lauscht: Auf das Gurgeln des Wassers unter den Eisenträgern der Jetée oder in Richtung des Boulevard Circulaire, auf dem der immer dichter werdende Autoverkehr jetzt in gleichsam stetigem Fluss von links nach rechts verläuft, mit einem dumpfen Grollen, das an das Brausen eines Ozeans vor dem Sturm erinnert.

Paris, November 2008. Observations sur la Défense. Enregistrement No. 13

Auf den Fliesenplatten zwischen den Bäumen auf der anderen Straßenseite, sind jetzt vier oder fünf Männer in Trainingsanzügen aufgetaucht, die sich einen Messerkampf zu liefern scheinen; eine breite kurze Klinge blitzt von Zeit zu Zeit in einer der Hände auf. Es liegt aber kein Grund zur Beunruhigung vor, denn nach einer Weile trennen sie sich unter Lachen und freundschaftlichem Schulterklopfen voneinander und gehen jeder seiner Wege. Zwei kleine Mädchen in rosa Strümpfen, weißen Schuhen, bis an die Nasenspitzen in bonbonfarbene Sportjacken gehüllt, biegen um die Ecke. Sie gehen schweigend nebeneinander her, jedes mit feierlicher Miene einen Hot-dog in fleckigem Papier vor sich hertragend. Die Bürger in Courbevoie behaupten gehässigerweise, es gäbe etliche Kinder im Viertel von Nanterre (aber auch in Puteaux), die, während noch sie Kinder seien, bereits solche zeugen und empfangen könnten, ihre Nachkommen wären dann allerdings von Geburt an Erwachsene. In jedem Fall kann der erste Eindruck trügen. Es gibt Motorradfahrer, Polizisten und Boulespieler, die alle auf den ersten Blick ganz normal wirken. Ihre Besonderheit liegt im Innenohr verborgen: Es reagiert außerst empfindlich auf die Fallwinde der Wolkenkratzer, deren Vibrationen in ihrem Gehirn eine schwermütige Trägheit erzeugen, die sie zu ewigen Bewohnern von La Défense macht.

Paris, Mai 2010. Observations sur La Défense. Enregistrement No. 23

Manche Fotografien lassen sich wie gewöhnliche Zimmer betreten: Hinter einer Tür, sagen wir, befindet sich eine Küche, dahinter ein Schlafzimmer, daran angrenzend ein sehr kleines Zimmer, in dem ein Bügelbrett an der Wand lehnt. Das Bad nebenan wird ausgefüllt von einer Frau, die in den Spiegel schaut. Ihre Haare sind feucht und hängen unordentlich über den Kragen ihrer Regenjacke. Die Frau, deren Gesichtszüge übrigens nur verschwommen zu erkennen sind, geht zurück in die Küche, stellt Wasser für einen Kaffee auf und schiebt den Vorhang des tränenförmigen Fensters ein Stück zurück: Man blickt auf einen Teil der Avenue Pablo Picasso: die Skulptur einer riesenhaften Python und, in Gebüschnähe, auf ein mit rotweiß gestreiften Markisen verkleidetes Provisorium aus Holzlatten. Doch auch hier kommt es auf den Standpunkt der Kamera an. Links unten im Vordergrund steht ein entblätterter Baum. Hinten leuchtet das Grün des Friedhofs, die frischen Blumen rosa und weiße Farbflecke, daneben eine riesige Anschlagtafel, auf der in roten Lettern die Worte „Réorganisation – Libéralisation – Idéalisation“ zu lesen sind. Der Vorhang fällt, ohne ihre Hand, wieder zurück; aber an der Fensterluke der Wohnung nebenan schiebt eine andere Hand eine andere Gardine zur Seite. Wieder etwas weiter stürzt, in der Nähe eines Geflechts aus Röhrenstrukturen, aus einem ovalen Fenster ein regelrechter Katarakt Regenwasser aus einer Höhe von etwa fünfzehn Metern auf das Pflaster.

Paris, undatiert. Tableau de Nanterre

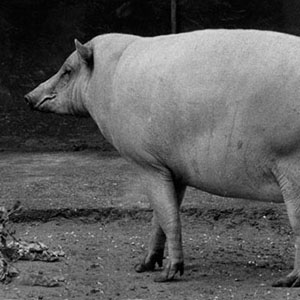

Auf der Brachfläche neben La Jetée hat sich eine Population von Salamandern häuslich eingerichtet. Sie leben in kleinen, aus Bruchholz und Steinchen zusammengefügten, mit Lehm verklebten Häusern. In der Nähe der an die Gärten der Arche anschließenden Mauer könnte man sogar fast von einer Salamanderstadt sprechen. An den wenigen verhältnismäßig trockenen Tagen sitzt der Melonenverkäufer auf einem Stück alter Karosserie und beobachtet die Salamanderfrauen, die ihre Kinderwagen ruckelnd über den brüchigen Asphalt schieben. Gegen 17 Uhr schält ein plötzlicher Sonnenstrahl ein polyedrisches Gebilde aus den Schatten. Den jeweiligen Standorten der Kamera nach zu urteilen, hat man den Eindruck, dass das Objekt jenes Autowrack ist, das nahe der großen Pfütze auf der rechten Seite mit dem Vorderteil in einer Lache rötlichen Schlamms liegt. Der Boden ist mit einem Muster unregelmäßiger Spuren bedeckt. Es scheint nur natürlich, dass unweit der Großen Arche eine wachsende Anzahl ungewöhnlicher Tierarten siedelt. In Nanterre wird von Hunden berichtet, die, statt zu bellen, sich angeblich einer geheimen Zeichensprache bedienen. Der seit Tagen nahezu unablässig fallende Regen hat die Gärten in Sumpfland verwandelt, willkommene Heimstatt für Scharen farbenprächtiger Wasservögel, die hier reichlich Nahrung finden. Ein Polizist gab unlängst die Sichtung eines Flachlandtapirs zu Protokoll, ein längerer Artikel im „Puteaux Commun“ folgte, das Einfangen des Tieres wurde allerdings durch die Kompetenzrangeleien der angrenzenen Kommunen vereitelt.