“The Madness” accompanies me since 2006 when I wrote it on request of the Frankfurt label Gruenrekorder. A handmade three-lingual edition was published on occasion of a presentation at the Titanik Gallery in Turku, Finland (“Through the Grapewine”, 2011). In 2015 it was accepted by Soundproof/ABC Australia for a perfected production and broadcast in 2016.

Excerpt:

Any documentarist must either be mad or go mad while pursuing her work. It might be very well to embark on a journey, but carrying along technical devices for the purpose of documentation is sometimes presumptuous and can lead you into the quagmire of self-humiliation, too. Not that it would be a question of falsehood, which is inevitably attached to any object of objectivity. But isn’t documentation, generally speaking, a kind of theft? Isn’t it like stealing from time? And, what’s more, isn’t it done in a more than awkward fashion considering the value of that which is documented? With regards to the total inadequacy of human perception, the question arises as to whether or not the obsessive pursuit of a particular goal must automatically leads to insanity. But a documentarist must turn mad just at the moment he or she realizes that something wonderful is happening… the videotape is at its end, the pencil broken, the aperture wrongly adjusted or simply the battery is dead. It has happened to many, but few have put it in writing: The failure of the ethnographer right in the middle of things. Compared to the total triumph that results from having captured something absolutely unique; something precious; the authentic copy of a stretch of time. The DNA of reality, a sequence of real-time. Holy real-time, mantra of the field-recordists. Lost! Lost!

Technical Failure 1: The Handsome Young Man

The minidisk recorder failed for the first time on a Sunday morning, 7th of July, on the occasion of a bus trip into a neighbouring village (which had been organized for journalists and interested individuals by the festival board). The bus stopped in front of a vestry equipped with a wooden stage and rows of chairs. The backdrop of the stage was adorned with a Finnish landscape painting in sparkling green and blue; cloudlets in the sky and a little brook. We were introduced to: the village choir, the music teacher (being prominently seated next to the piano), some little nippers with violin and accordion at a tender age ranging from five to seven years, and a handful of young talents from the vicinity. Now there was an exception, a boy of maybe 16 years who, when you just looked at him, caused something in your heart to tremble. This, as far as I could see, was due to the delicate features and lines around his mouth which was straight but still the most mobile part of his face. His accordion-playing was without question first class, and consisted of only two short pieces. Each single tone, each note appeared as an innermost expression in his face and only after that were they emitted as sound from the instrument. Naturally, such an instance happens much too fast to perceive and name it consciously – only by memory can one slow it down and retrieve it in fragments. I had put the broken machine aside and was totally absorbed in this much too short contemplation. His face remained, while he played, perfectly naked and sensitive, but so deeply immersed as to be unreachable.

Deleted No. 1. Eero Peltonen sings the “Song of the Happy Squirrel”

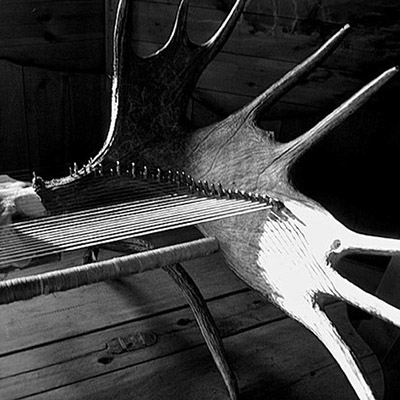

Did I talk about the aura of technical disaster in the beginning? Well, now my head is again veiled by a dark cloud, quite similar to a mosquito-cloud and I am being heavily pestered by the vile, derisive hum of failure in my ears. Beform my inner eye: visualizations of finger tips on wrong buttons, the fall of technical devices from tables and rocks, malfunctions of in- and outputs, and in between, the gaping black gorge of forgetfulness. Therefore, it is now time for Laulu Oravasta the “Song of the Happy Squirrel”: A squirrel sits in its cove high up in a tree and it looks down onto the world. But all it sees is death and murder and other evil things happening on earth. The squirre| is very frightened, but then it looks another way. Right before its nose, the tree stretches a big branch out into the open air, green and green with rustling leaves. Just like a beautiful big flag, thinks the squirrel and continues watching the swaying branch. By now, the whole tree has started to sway, and the squirrel feels warm and comfy. The trees rocks the squirrel in ivs cove like a mother rocks her baby to sleep. All the trees of the forest move with the wind and the whispering of the leaves makes the forest sound like a kantele, Metsän kantele, the kantele of the forest. At the end, it looks up through all the leaves and branches into the sky. Birds are floating in a huge flock through the blue, singing. And the squirrel feels very happy.

The song is a famous poem by Aleksis Kivi, the first Finnish writer who dared in 1870 to publish a novel in his mother tongue (and not in the formerly prescribed official language that was Swedish). Eero says, of course everybody would talk about Kivi’s novel „The Seven Brothers“, but his songs would also be very beautiful. The squirrel song has a rather simple melody; at the end of each verse, Eeros voice comes down to a deep bariton, vibrating on a single tone and then starting anew. The song ends very low somewhere in the bass notes – and that was the moment I started to cry. Heart of wax, perhaps, who could tell.